1. Start here. Woodworking 101

3. The Ultimate Outdoor Pavilion Guide – Permits, Framing, and Roofing

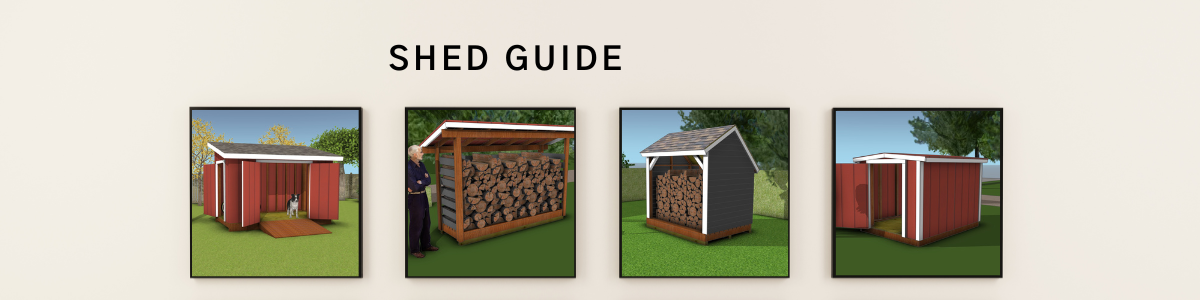

4. The Ultimate Shed Building Guide – Permits, Framing, and Roofing

5. DIY Chicken Coop and Raising Chickens: A Comprehensive Guide

6. Building a Greenhouse in the USA: A Beginner’s Guide

Sheds have become an essential addition to many homes, serving as everything from humble storage spaces to stylish home offices. They offer a dedicated spot to stash gardening tools, holiday decorations, and seasonal gear – freeing up your garage or basement and keeping your home clutter-free. Beyond storage, a well-built shed can be a workshop for DIY projects, a place to unleash your hobbies, or even a quiet backyard retreat. In fact, having a shed adds versatility and value to your property, often impressing potential buyers by indicating extra usable space on the lot. Simply put, a shed is more than four walls and a roof – it’s a game-changer for your home and lifestyle.

Building or upgrading a shed is an exciting DIY project, but it comes with important considerations. This comprehensive guide will walk you through everything you need to know – from understanding permit requirements and choosing the right framing method, to selecting a roof style and materials, laying a solid foundation, creating a handy loft space, and even converting a shed into a cozy home office. We’ll share practical tips, real-world advice, and best practices at each step, all in a friendly, engaging tone. By the end of this guide, you’ll be fully equipped (and inspired!) to plan and build the ultimate shed that perfectly suits your needs. Let’s get started!

Permit Requirements in the U.S.

Building a shed may seem like a small project, but it’s crucial to tackle the legalities first. Permits ensure your shed meets safety standards and local zoning laws . The last thing you want is to put time and money into a beautiful new shed only to face fines or an order to tear it down because it wasn’t permitted correctly. So, do you always need a permit? The answer: it depends on your location and the shed’s specs. Here’s an overview to help you navigate shed permit requirements in the United States.

When Is a Permit Needed?

In many areas, very small sheds don’t require a building permit. Sheds under a certain size (often around 100 to 120 square feet) are commonly exempt from permits, while larger structures usually need one. For example, some municipalities let you build a shed up to 120 sq ft with no permit, but anything larger triggers the permit process. Other places set the bar higher (200 sq ft is another common cutoff or lower – always verify what applies in your area. Keep in mind that even if a building permit isn’t required for a tiny shed, you may still need to meet zoning rules like setback distances from property lines or maximum height limits.

Several factors determine if you need a permit besides just square footage. Local codes might consider:

- Shed Height: An unusually tall shed could need approval. (For instance, Indianapolis mandates a permit if a shed is over 15 feet high.

- Foundation Type: A shed on a permanent concrete slab or with footings might require a permit where a skid-mounted shed might not.

- Utilities: If you plan to wire your shed with electricity or plumbing, permits are typically required regardless of shed size. Running power, installing outlets/lights, or adding a water line means you’re extending your home’s systems, which must be inspected for safety.

- Intended Use: A basic storage shed has different implications than a shed used as habitable space. Using a shed as a living space, guest room, or home office could invoke stricter rules. Some areas treat sheds with sleeping quarters or intensive use as accessory dwellings, which have tighter regulations.

- Location on Property: How close the shed sits to your property line, fences, or the street can affect permit needs. Many locales require sheds to be a certain number of feet away from property boundaries. If you place a shed too close, you might need a special zoning permit or variance. Always check local setback requirements in your zoning code.

- Homeowners Association (HOA) Rules: Aside from city/county laws, if you have an HOA, they might have their own approval process, size limits, or style guidelines for sheds.

The general rule is: assume you need a permit unless you confirm otherwise. Even if your shed is small, it’s wise to double-check the regulations. Permit thresholds can vary widely. One town might allow a 10’x12’ shed with no permit, while the next town over insists on paperwork for anything bigger than a doghouse. As one shed expert notes, some jurisdictions exempt all sheds under 120 sq ft, while others require permits for any accessory structure regardless of size. The only way to know for sure is to research your local codes.

How to Check Local Requirements

Navigating permits might sound intimidating, but it’s usually straightforward. Start with your city or county’s building department or planning and zoning office. Most have websites with a section on residential permits or even specific info about sheds. Look for terms like “accessory structures” or “storage buildings” in their guidelines. You’ll often find exactly what size is exempt and what conditions apply. If the information isn’t clear online, don’t hesitate to call the building department directly – they’re there to help. Explain the size and planned use of your shed and ask what permits (if any) are required.

Tips for checking permit requirements:

- Browse Official Resources: City/County websites often publish a summary of permit rules. For example, many jurisdictions follow the International Residential Code (IRC) which exempts one-story sheds under 200 sq ft, but local amendments can override this. Some counties list common projects that don’t need permits (e.g. “sheds under X square feet, no utilities”). Always read the fine print.

- Ask Neighbors or Contractors: If you know a neighbor who built a shed or a local contractor, they might shed light on the process. Just be sure to still verify the info, since codes can update.

- Zoning vs Building Permits: Understand that even if a building permit isn’t needed due to small size, a zoning permit or at least adherence to zoning rules is still necessary. Zoning deals with where you can place the shed on your lot, its height, and usage. Building deals with how it’s constructed. So your shed might skip a building inspection but still has to follow zoning laws (setbacks, etc.).

- Prepare Basic Plans: When you inquire, have details ready: the shed’s dimensions, location on your property, and if you’ll add electricity/plumbing. This helps officials give you accurate guidance. They may tell you that a simple site plan sketch is needed for approval, for instance.

Getting a permit isn’t just red tape – it actually protects you. With a permit, an inspector may check that your shed is structurally sound and not endangering anyone. It also ensures the shed is recorded for future property sales. An unpermitted structure can complicate selling your home or even invalidate insurance claims if something goes wrong. In short, doing it by the book is worth it for peace of mind.

Consequences of Skipping Permits

It might be tempting to “build now, ask later,” especially for a small shed, but be careful. Ignoring permit requirements can lead to serious headaches. Municipalities have the authority to enforce building codes, and if they discover an unpermitted shed, you could face fines, penalties, or forced removal of the structure. Fines vary by location but can be hefty – ranging from a few hundred dollars to thousands, sometimes even accruing daily until the shed complies. In worst-case scenarios, authorities might require you to tear down the shed or cease using it until it’s brought up to code.

Keep in mind: neighbors or passersby may report unpermitted work if they’re concerned (or unhappy) about it. All it takes is one complaint to bring an inspector to your door. Additionally, if you ever plan to sell your home, an unpermitted shed can show up as a red flag during the inspection or title process. You may be forced to retroactively permit it (if possible) or remove it before closing a sale.

The bottom line is, permits protect you and your investment. They ensure the shed is safe and up to code, and they prevent costly issues down the road. So, before you start building, take that extra step to check requirements and secure any needed permits. It’s a small hassle now that can save you a big headache later. As the saying goes, better safe than sorry!

Quick Recap: Most areas require a permit for sheds larger than about 100–200 sq ft, or any size if you’re adding electrical/plumbing. Always verify local rules, as they vary. Apply for permits as needed by submitting your plans to the city/county. Once approved, display the permit on-site (if required) and call for any necessary inspections at the proper stages (for example, an electrical inspection if you wired the shed). By following the permit process, you’ll build with confidence and avoid legal troubles. Now, with the paperwork out of the way, let’s move on to the fun part – building your shed strong and sturdy!

Framing Techniques and Options

With permits squared away, it’s time to build. The frame of your shed is its skeleton – it gives the shed shape and strength. A well-framed shed will stand straight and sturdy for years, through wind and weather. In this section, we’ll focus on wood framing (the most common DIY method) and explore a few framing techniques: stick framing, post-and-beam framing, and pole framing. Each has its pros and cons, and the best choice depends on your shed’s size and purpose, as well as your skill level. We’ll also cover some best practices to ensure your shed frame is durable and strong no matter which method you use.

Stick Framing (Platform Framing)

Stick Framing: This is the go-to method for most standard sheds and is very similar to how houses are built. In stick framing, you construct walls from many smaller pieces of lumber (“sticks”). Typically, you use 2×4 or 2×6 studs spaced 16 inches on center to form the vertical wall supports. These vertical studs attach to horizontal top and bottom plates, and additional pieces frame out openings for doors and windows (including headers over those openings for support). The walls are usually built flat on the shed floor deck and then raised upright into position. Once the walls are up, ceiling joists or roof rafters tie them together at the top.

Stick framing is popular because it’s straightforward, uses readily available materials, and is fast for small structures. Even a novice DIYer can frame a basic shed wall with some planning and patience. It’s also economical – 2×4 lumber is affordable, and you only use as much wood as needed for structural support. Another big advantage is that stick-framed walls provide convenient cavities for insulation if you plan to finish the interior (important for a shed workshop or office).

Despite being “lighter” than other methods, a stick-framed shed can be very sturdy if built correctly. Use pressure-treated lumber for any parts that will be near ground moisture (like the bottom plates) to resist rot. Make sure to install proper bracing: sheathing the walls with plywood or OSB adds rigidity and prevents racking (the whole frame skewing in a parallelogram shape). You can also add metal hurricane ties or diagonal braces for extra wind resistance. One thing to watch is that stick framing relies on many nail connections, so take your time to ensure each connection is secure. When done right, this method yields a strong, stable shed frame that can easily support siding, roofing, and even a small loft.

Best for: Sheds of most sizes (especially common for 8×8 up to 12×20 or more). It’s ideal for DIY builders due to its simplicity. If your shed is on the smaller side, stick framing is usually the quickest way to get it built.

Example: Imagine a 10×12 garden shed. With stick framing, you’d lay out a floor deck (let’s say on skids or joists), then nail together 2×4 studs into four wall panels. Each wall might have a door or window opening framed in. You’d raise each wall and nail them together at the corners, then add roof rafters on top. In a weekend or two, you have the basic structure – all with standard lumber and tools. That’s the beauty of stick framing: it’s like building with an Erector set made of wood.

Post-and-Beam Framing (Timber Framing)

Post-and-Beam Framing: Post-and-beam (also known as timber framing) is a more old-fashioned technique, but it makes for an incredibly robust shed. Instead of many small studs, this method uses a few heavy posts and beams to create the frame. Think of it like a barn or timber lodge style. You might have 4×4, 4×6, or even larger posts at the shed corners and at intervals in between, connected by hefty beams that run horizontally. These form the outline of the walls. The posts carry the load of the roof directly down to the foundation, so you don’t need as many wall studs in between (often just enough to attach siding or fill wide gaps).

One immediate benefit: a post-and-beam frame has fewer pieces, so it can create a more open interior space. This is great if you want a spacious feel or plan to use the shed as a workshop where bumping into closely spaced studs isn’t ideal. Fewer pieces also mean potentially faster assembly of the main structure – but those pieces are much heavier. Handling a 6×6 timber and holding it plumb can be challenging solo. Often, this method is better for somewhat larger sheds (e.g. a big 16×20 storage shed or small barn) where the extra strength is needed.

Traditional timber framing involves fancy joinery like mortise-and-tenon joints to fit posts and beams together without metal fasteners. If you’ve seen old barns, they use wooden pegs in pegged joints. However, you don’t have to go full 18th-century craftsman for your shed. Modern post-and-beam construction can use metal connectors, like heavy steel brackets, plates, and thru-bolts to secure posts to beams. For example, you might use post cap brackets to tie a beam on top of an upright post. This simplifies construction while still giving you that robust frame.

Post-and-beam framing results in a sturdy, long-lasting building. Thick posts resist rot longer (especially if they’re treated or naturally rot-resistant wood) and can support substantial weight. This is why larger sheds or garages often use this style – it scales up to big structures more easily than stick framing, which would require very many studs and possibly interior load-bearing walls. Aesthetically, if you plan to leave the interior exposed, big timbers have a nice rustic look.

Downsides? Cost can be higher because larger lumber and hardware are pricier. It’s also labor-intensive in terms of precision – you must get posts and beams aligned perfectly square and plumb, otherwise the whole frame is off. And as mentioned, the pieces are cumbersome; raising a post-and-beam wall might take a couple of strong friends or some rigging, whereas a stick-framed wall can often be lifted by one or two people.

Best for: Larger sheds (over 200 sq ft) or those where you want a barn-like durability. If your shed might house a heavy load (like a lot of equipment or even a vehicle in a small garage), post-and-beam ensures the structure can handle it. Also, if you’re going for a particular look (rustic cabin or mini-barn), this framing fits the bill.

Pole Framing (Post-Frame Construction)

Pole Framing: Often used interchangeably with “post-frame,” this technique is what you see in many pole barns and farm sheds. It’s a cousin of post-and-beam but even more simplified. In pole framing, the primary support posts are embedded directly in the ground (or set into concrete piers in the ground) rather than onto a traditional foundation. For example, you might sink 4×4 or 6×6 posts at the shed’s corners and midway along the walls. These posts stand vertically and act as the shed’s legs, so to speak. Then you attach beams or “girts” horizontally between the posts to tie them together and support the siding and roof.

One method is to set round poles or pressure-treated posts into holes (with concrete backfill for stability), then nail horizontal boards (called girts) across them to later attach siding. Another method is to use square posts and actually frame wall sections that fit between the posts. Either way, the vertical poles take the structural load.

The advantage of pole framing is that you don’t need a full concrete foundation or floor. The posts in ground serve as the foundation. You can even build the shed without any floor initially (just a dirt or gravel floor), which is common for agricultural sheds or run-in shelters. This makes it cost-effective – you save on concrete and extensive site work. It’s also very forgiving on uneven ground; you can cut each post to height after setting them so that you end up with a level roof line even if the terrain slopes.

Pole framing is great for large, open structures. It was mentioned that very large sheds (like those needing a huge open interior for livestock or machinery) often use pole construction. For a backyard shed, you might choose this if you want a quick build and don’t mind the look of interior posts. It works best when the shed’s floor doesn’t need to be raised wood framing – for instance, you could later pour a concrete slab inside, or just use gravel.

Durability considerations: Because the posts are in contact with soil, they must be properly treated or naturally rot-resistant (like cedar or ground-contact rated lumber) to last. Also, anchoring them deeply (below frost line in cold regions) is important to prevent frost heave. Many pole barn builders bury posts 3-4 feet deep or more, often with a concrete footing or cookies at the bottom of the hole for stability.

One more thing: since pole framing doesn’t automatically include a floor deck, if you do want a wood floor, you’d still have to frame that between the posts or pour a slab. So it’s a bit of a hybrid approach.

Best for: Sheds on farms or large yards where function matters more than a finished interior. Also, when a concrete slab is not in the budget or you want to avoid major excavation. A small pole-framed shed could literally be just four posts in ground with a roof and minimal walls – extremely quick to put up for basic storage.

General Framing Best Practices

No matter which framing style you choose, a few golden rules will make your shed last longer:

- Use Treated Lumber at Ground Contact: The lowest parts of your shed (like the skids, floor framing, or posts if using pole framing) should be pressure-treated to resist moisture and insects. This prevents rot in the most vulnerable areas. Even better, design your shed so no wood directly touches soil – use concrete blocks, piers, or gravel underneath as a buffer.

- Keep Framing Square and Plumb: Constantly use a level and a framing square during construction. A square, level frame means everything else (siding, roofing) will go on easier. If you can, cross-brace the walls temporarily while building to hold them true. Measuring corner-to-corner diagonals of wall panels can ensure they’re square before you stand them up.

- Secure Connections Properly: Use the right fasteners and connectors. Galvanized nails or structural screws are best (regular interior drywall screws, for example, are too brittle). For critical joints like where roof rafters meet the top plate, consider metal hurricane ties or brackets. These inexpensive connectors can greatly increase wind resistance. Bolts are preferable for post-and-beam joints or securing posts to foundations.

- Sheathe for Shear Strength: Adding plywood or OSB sheathing to your framed walls (at least on the corners) turns your frame into a rigid diaphragm, meaning it won’t wobble. Even if you plan to use decorative siding, a layer of sheathing underneath is highly recommended for strength and as a base for a weather barrier.

- Don’t Skimp on Fasteners: A common DIY mistake is not using enough nails or screws. Follow guidelines like “2 nails per stud at each plate” etc. Each stud-to-plate connection, each piece of blocking – secure them properly. It all adds up to a solid structure. Also, attach walls to the floor or foundation firmly (through bottom plates into the floor framing or anchors in slab). Your shed should essentially become one interconnected unit.

- Plan for Openings: Frame door and window openings with appropriate headers that can carry the load above. For a shed, a single 2×4 or 2×6 header might suffice for a window, but for wide double doors you may need a built-up header (like a sandwich of two 2x6s with plywood). Make sure you include “jack studs” (aka trimmers) under each end of a header to transfer weight down to the sill. These details ensure your doors and windows won’t bind and your roof load is properly distributed.

- Consider Future Needs: If you might add shelves, a loft, or hang tools, think about adding extra blocking or studs where needed. It’s easier to reinforce now than retrofit later. For example, if using stick framing, you can include blocking between studs at 4 feet high around the interior, giving you solid wood to mount shelves onto anywhere along the wall.

Framing is literally the backbone of your shed. Taking the time to do it carefully will pay off with a building that feels solid and safe. And don’t be afraid to modify or combine techniques – some shed builders use stick framing for the walls but beefier posts at corners (a hybrid between methods). The goal is simply to create a strong structure that suits your needs. With your frame up, you’re ready to move to the next steps: adding a roof over that frame and securing it against the elements. Speaking of which, let’s talk about roofing options!

Roofing Shapes, Slopes, and Materials

The roof is one of the most defining features of your shed’s look and function. Not only does it protect everything below from rain and snow, but the shape and slope of the roof affect how well water runs off, how much headroom or storage space you have inside, and the overall aesthetic of your shed. There are many roof styles to choose from – each with its own charm and practical advantages. In this section, we’ll cover the major roof shapes (like gable, hip, gambrel, and more), discuss roof slopes/pitch and why they matter, and compare popular roofing materials you can use (asphalt shingles, metal panels, wood shakes, polycarbonate panels, etc.). By understanding these elements, you can design a shed roof that not only looks great but also suits your climate and usage needs.

Major Roof Shapes

Sheds can sport nearly any roof style that houses do (and a few that houses usually don’t!). Here are the most common roof shapes you’ll encounter, with their key characteristics:

Gable Roof: The classic gable is what most people picture as a traditional roof. It has two sloping sides that meet at a central ridge, forming a triangular “gable” wall on each end . On a shed, a gable roof is popular because it’s simple to build and highly effective at shedding water. Imagine an A-frame of rafters or trusses sitting on your shed walls – that’s a gable. Pros: Good runoff for rain and snow (especially if you choose a decent pitch like 4/12 or higher), a bit of overhead storage or attic space along the ridge, and straightforward construction with common techniques. Gable roofs also lend themselves to ventilation; you can vent the attic space at the gable ends or add a ridge vent easily. Cons: They do create higher walls at the ends and lower headroom near the side eaves inside. In very high winds, gable roofs can catch wind like a sail, so proper anchoring and perhaps hurricane ties are important. Overall, a gable roof is a fantastic all-purpose choice for a shed, balancing simplicity and performance.

Hip Roof: A hip roof slopes down on all four sides of the shed, so there are no vertical gable walls. The sides converge at a ridge or a single point if it’s a small square roof. Think of a pyramid-like shape (if square) or a truncated pyramid (if rectangular, with a short ridge across the top). Pros: Hip roofs are very stable in high winds because all sides slope down – no big flat gable ends for wind to push against. They also have eaves on all four sides which can help protect the shed’s walls from rain. Visually, a hip roof can make a shed look more like a little cottage or pool house (great for blending into landscaping). Cons: They are more complex to build. The roof framing involves angled cuts for the hip rafters and jack rafters, or special trusses, which is a bit advanced for beginners. There’s also slightly less useable attic space, as the roof slopes in from all sides. Ventilation can be trickier – you might need roof vents since there’s no gable for gable vents. A hip roof also typically requires more material (more rafters, more sheathing) so it can be a tad more expensive. Use a hip roof if you’re confident in your framing skills or are going for a certain look, especially in windy or hurricane-prone areas where that extra stability pays off.

Gambrel Roof: Often called a barn roof, a gambrel is the iconic two-stage slope roof seen on traditional barns (as in the image above). Each side of the roof has two pitches: a steep lower section and a shallower upper section, meeting at the ridge. This creates that lovely curved profile (actually angular, but appears curved). Pros: The shape maximizes interior space. A gambrel roof gives you a much taller ceiling and often an entire loft area, because the steep lower slopes make the walls feel higher and the shallow upper slopes still provide weather protection. If you want a storage loft or even a small second level in your shed, a gambrel is ideal – you can easily gain overhead storage equal to 40% or more extra space. Aesthetically, gambrels have tons of character (that classic red barn shed above certainly exudes country charm). Cons: They are more complex to build than a single-slope roof. You’ll need to fabricate trusses or rafters with an angle (pitch break) in them, often using gussets or metal plates at the joints. Weatherproofing can be a bit more involved: the change in slope creates a “break” line along the roof that needs proper flashing or overlap to avoid leaks. Also, like gables, the gambrel has gable ends that catch wind, so bracing is important. In heavy snow areas, gambrels do shed snow but you must ensure the steep lower section is sturdy, as snow can sit on the upper part and put outward pressure at the pitch break. With good plans (there are many shed gambrel plans available) these issues are solvable. Many people’s favorite sheds are gambrel style because of the roomy loft and distinctive look.

Lean-To (Single-Slope) Roof: A shed roof (yes, confusingly the shape is called a shed roof) or skillion roof is basically a single flat plane that slopes in one direction. One wall of your shed will be higher than the opposite wall, and the roof boards or rafters just span between them at an angle. It’s like taking a gable roof and removing one half. Pros: Easiest roof to build, hands down. Fewer cuts and angles – often just common rafters all the same size, laid across. It requires the least material and can be very cost-effective. A lean-to roof is great for small sheds or when you want to build the shed against another structure or fence. It also lends a modern look – many contemporary studio sheds use a single-slope roof. Water runs off one side, so you can position that slope strategically (for example, away from a fence or towards a garden that needs watering). If oriented properly, a single-slope roof can accommodate solar panels nicely due to the broad uniform surface. Cons: Because the slope is usually fairly low (often 2/12 to 4/12 pitch), it’s not ideal for heavy snowfall unless you beef up the structure. Ventilation can be an issue since there’s no ridge – you may need to vent through the high wall or use soffit vents at the low end and maybe a vent at the top of the high wall. Another consideration: the high side of the shed will have a taller wall (good for headroom), but the low side wall might be quite short, so plan your door placement accordingly (usually on the tall side or an end wall). Also, with a low-pitch roof you must choose the roofing material carefully to prevent leaks (we’ll cover this soon). Overall, a lean-to is perfect for simple storage sheds and offers a clean, unobtrusive profile.

Other Roof Styles: There are a few more styles you might come across, though less common for DIY sheds:

- Saltbox Roof: This is basically a lopsided gable – one slope long and shallow, the other short and steep. It has a charming asymmetrical look and was used in colonial architecture. On a shed, it’s mostly aesthetic (adds character) since the interior headroom is uneven. It’s reasonably easy to build (like a gable with different pitches on each side).

- Mansard Roof: Think French architecture – like a gambrel but on all four sides (basically a hip + gambrel combo). You get a flat or gently sloping top and steep lower slopes on all sides. It yields a lot of attic space but is complex to build and probably overkill for a small shed (rarely seen in sheds due to complexity).

- Flat Roof: A truly flat roof is not recommended for sheds in most climates, but a very low-slope roof (like 1/12 pitch) might as well be flat. Some ultra-modern shed designs use this, but you must use appropriate materials (like a continuous membrane) to waterproof it. Flat roofs do allow you to potentially garden on top (green roof!) or have a deck, but again, that’s advanced territory for sheds.

- Combination Roofs: Some sheds combine styles, like a gable with a small hip on the ends (called a Dutch gable), or a gable with a secondary lean-to section (if an L-shaped shed). These can solve specific needs (like wrapping a shed around a corner or matching house rooflines) but generally involve more planning.

Choosing a roof shape comes down to balancing practical needs and aesthetics. If you need maximum storage or even a loft sleeping area, gambrel wins. If you want easy construction, lean-to is king. If you’re matching your house’s roof or want a refined look, maybe hip or saltbox. Also consider your neighborhood or HOA – occasionally, there are rules about shed roofs matching the house style. On the practical side, think about weather: lots of snow -> avoid flat-ish roofs; lots of wind -> maybe avoid tall gables or ensure extra reinforcement.

Roof Pitch and Why It Matters

Roof “pitch” or slope refers to how steep the roof is. It’s usually given as a ratio of rise over run (in inches per foot). For example, a 4/12 pitch means the roof rises 4 inches vertically for every 12 inches of horizontal span. Slope can also be given in degrees, but in construction the ratio is more common. Why does pitch matter? Water drainage and durability. Steeper roofs shed water (and snow) more quickly, which generally means fewer leaks and less weight sitting on your shed. However, steep roofs have their downsides – they use more material (bigger gables, more lumber), and if too steep, they can be harder to build and climb on for maintenance.

Different roof shapes have typical pitch ranges. Gable roofs on houses, for instance, often range from 4/12 up to 12/12 (45 degrees) or even more for alpine areas. For sheds, you might see anything from a shallow 2/12 up to a steep 12/12 depending on style.

Why choose one over the other?

- Low Slope (Flat to ~3/12): If you’re aiming for a low-profile shed or using a material like metal or rolled roofing that can handle low slopes, this might be okay. But be cautious: standard asphalt shingles usually require a minimum slope of 2/12 or 3/12 to avoid leaks. Anything less and water can seep under shingles because it doesn’t run off fast. Low slopes are easier to walk on and build (you won’t slide off), and they reduce the total height (maybe important for zoning or visibility). Just remember to beef up your waterproofing. Often, builders will lay down an ice & water shield or even a rubber membrane on low slopes under the shingles for extra protection. If using corrugated metal, low slopes are generally fine as long as you overlap panels properly. One cool thing: a low slope can give your shed a modern “flat roof” look which some people prefer.

- Moderate Slope (~4/12 to 6/12): This is a sweet spot for many sheds. It provides good runoff, meets all material requirements, and is still fairly easy to build. Most prefab sheds with gable roofs are somewhere around 5/12 pitch, which looks good and performs well. At this range, you can use shingles confidently, and snow will usually slide off once it melts a bit. Headroom inside along the center is decent if you want to stand or have a small loft for light storage.

- Steep Slope (8/12 and above): Now you’re getting into dramatic roof territory. Steeper roofs dramatically increase overhead space (for example, a 12/12 roof on an 8-foot wide shed gives you a peak around 4 feet above the wall height – potentially allowing an adult to stand at the center). If you plan a loft, steep is great. They also shed precipitation extremely well – snow practically slides right off a metal 12/12 roof when the sun hits it. However, building the roof with rafters at sharp angles means carefully cutting ridge angles, birdsmouths, etc. and working on a steep incline. You might need roof brackets or scaffolding to be safe while sheathing and shingling a steep roof. Also, note that a very tall roof might make the shed exceed height limits or just look a bit out of proportion to the base (unless that’s the style you want).

One important consideration: Climate. If you live in an area with heavy snowfall, building codes often specify a minimum roof load that essentially pushes you toward a steeper pitch or stronger rafters. Snow that doesn’t slide off must be supported. Either you go steeper so it slides off, or you use heftier rafters/trusses on a shallower roof. In rainy climates, avoiding very low slope keeps rain from pooling. In windy areas, strangely, a moderately pitched roof can perform better than a flat one (less uplift than a flat eave) – but too steep can add drag. It’s a balance.

From an aesthetic perspective, try to match the pitch to your house or surrounding structures if you want harmony. If your home has a 6/12 roof, a 6/12 shed will subtly feel cohesive. Alternatively, contrasting a low-slung shed against a high-peaked house can make the shed less noticeable, which might be good if you want it to blend with the fence line or garden.

A quick tip: use a speed square or an online calculator to figure out your rafter lengths and pitch angles. If math isn’t your thing, many shed plans come with pre-calculated rafter templates for common pitches.

To summarize, roof slope affects:

- Water/Snow Management: Steeper = better runoff, less standing load.

- Material Choice: Shingles need ≥2/12, ideally ≥3/12; metal or roll roofing can go lower.

- Interior Space: Steeper = more volume overhead (potential loft).

- Looks: Steeper = taller/more imposing; shallow = sleek/modern or unobtrusive.

- Build Difficulty: Steeper = more challenging to work on; shallow = easier.

Most shed builders choose something in the middle unless they have a specific goal. For instance, a gable 6/12 roof with asphalt shingles is a very safe, conventional choice that will serve well in most places. If unsure, that’s a good default. You can always tweak from there based on your priorities.

Now that you have a roof shape in mind and an idea of how steep it will be, let’s explore the actual roofing materials – what you’ll cover that roof with. The material will interact with the shape and slope (as we noted, some materials suit certain pitches), so it’s an important decision both for functionality and appearance.

Roofing Materials: Options and Comparisons

Just like there are many roof shapes, there are numerous materials to cover your shed’s roof. The “right” choice depends on your budget, desired look, climate, and how much maintenance you’re willing to do. Here we’ll look at four popular options for shed roofing: asphalt shingles, metal roofing, wood shakes/shingles, and polycarbonate panels, plus a mention of others like rubber membranes and tiles.

Asphalt Shingles: This is by far the most common roofing for houses in the U.S., and it’s popular for sheds too. Asphalt shingles are those paper-backed or fiberglass-backed shingles coated with asphalt and stone granules. They usually come in 3-tab or architectural styles (architectural being thicker, dimensional shingles). Pros: Shingles are affordable and easy to install – great for DIY. They offer decent durability (typically 20+ years lifespan for basic ones). They handle moderate wind and rain well and come in a variety of colors to match your home. They also provide a classic look; your shed will look like a miniature house. Cons: On sheds with low slope (below 2/12) shingles are not suitable because they can leak. They are also a bit heavy (not usually an issue for small roofs, but something to note). In damp climates, shingles might grow moss or algae over time (you might notice on north sides of roofs). This is cosmetic but can shorten their life if not cleaned periodically. Also, shingles can be torn off by very high winds if not properly nailed and if the shed is very exposed. However, if installed per instructions (with the proper number of nails each, and maybe some roofing cement at edges in wind-prone zones), they perform well. Installation Tip: Put down roofing felt or underlayment over your shed roof sheathing first, then shingles. And ensure overlap and staggering are done correctly. With a utility knife and hammer, most shed owners can shingle a small roof in an afternoon. Many find that matching the shed’s shingles to their house’s shingles creates a nice cohesive look.

One caution: If your shed roof is below 3/12 pitch, you should take extra measures or choose a different material. Some shingle manufacturers allow down to 2/12 pitch if you use an ice & water shield (sticky membrane) over the whole roof deck and then shingles, but below 2/12 they won’t warranty leaks. So, plan slope accordingly if you want shingles.

Metal Roofing (Corrugated or Standing Seam): Metal panels are a fantastic option for sheds, and they’ve become very popular for both rural and modern aesthetic sheds. These could be classic corrugated galvanized steel panels, more modern ribbed panels with baked-on colors, or even high-end standing seam panels. Pros: Metal roofs are extremely durable (often 30-50 year lifespan or more) and low-maintenance. They excel in snow and rain – snow slides off and rain runs off fast. They also can handle low pitches; even at 1/12 or 2/12, many metal roofing systems are waterproof if installed correctly (with proper overlaps and sealants). Metal is fireproof (important if, say, you’re in a wildfire-prone area or just using a fire pit nearby). Installation can be quicker than shingles since you’re placing large panels (you do need to cut them to length and be careful with edges). Cons: Upfront cost is higher than shingles, especially for thick gauge or standing seam styles. But since shed roofs are small, many DIYers splurge on metal since the total square footage isn’t huge. Metal roofs can be noisy in rain/hail – on a shed this might not matter much unless you’re inside it during a storm (some people actually like the sound of rain on a metal roof). Also, metal roofs require care to avoid scratching the finish (for colored panels) and you’ll want to install foam closures or mesh at ridges and eaves to keep out wasps or wind-blown rain. Another consideration: condensation. If the shed is uninsulated, moist air can condense on the underside of a metal roof in certain conditions, causing drips inside. You can combat this by adding a vapor barrier or using insulated metal panels, or simply ventilating the shed well. For most storage sheds, not a big issue. In terms of looks, metal can give a utilitarian vibe (e.g. a simple corrugated roof) or a sleek modern vibe (flat panel standing seam). And colors! You can get metal roofing in many colors to match your palette.

Perhaps the biggest draw: no leaks (if installed right). You don’t worry about blown-off pieces or water seeping through overlaps if you follow the instructions.

Wood Shingles/Shakes: For a truly quaint, rustic look, wood shingles or shakes are an option (cedar is most common). These are natural wood pieces, either sawn (shingles) or split (shakes), layered on the roof similar to how shingles are laid. Pros: Aesthetic charm – a cedar shake roof on a shed can make it look like an old-world cottage or a storybook house. Cedar and redwood are naturally rot-resistant and insulating. If untreated, they weather to a silvery gray that some find beautiful. They are also lightweight and renewable resource. Cons: Maintenance and longevity. Wood roofs can be prone to moss, mildew, and decay over time, especially in damp climates. They often last 20-30 years on a house roof, but on a shed you might see less if not cared for (since sheds might not have the same ventilation or steep pitches houses do). They must have a good slope (definitely 4/12 or more) to shed water and dry out, otherwise they’ll leak or rot quickly. Some areas restrict wood roofs due to fire hazard (dry cedar is more flammable, though treatments exist). Installation is more labor-intensive than asphalt shingles (lots of pieces to lay, with specific spacing for expansion). Cost can be higher too, depending on the grade of wood. If you love the look, one compromise is to do a wood shake roof over plywood and felt (for backup waterproofing). Or, use wood shingles on the walls of the shed for the look, but use a different roof material that you can’t easily see – that way you get style and performance. All that said, many historic sheds (think old barns or cabins) had wood roofs, and they certainly work if you’re committed to the aesthetic. Just plan on checking them every so often, removing debris that lands on them, maybe treating with a wood preservative every few years to prolong life.

Polycarbonate Panels: These are clear or translucent panels often used in greenhouses or patio covers. You might consider them for a shed if you want to let light in through the roof – for instance, if part of your shed will be a potting area or you want a skylight effect. Polycarbonate panels (like corrugated plastic panels) are virtually unbreakable and much tougher than acrylic or glass. Pros: Lightweight and easy to handle, lets natural light in (could even make a fully daylit shed or greenhouse hybrid), and fairly durable – many are rated for 10-20 years with UV resistance. They install similarly to metal roofing (overlapping panels), and can be used on low or steep slopes (just seal well on low slopes). Polycarbonate won’t rot or rust. It’s also flexible and can be cut with snips or a fine saw easily. Cons: Insulation is not great – polycarbonate doesn’t insulate much (though twin-wall panels do better). So if you need the shed to hold heat or cool, a clear roof isn’t ideal. They also can discolor over time (cheaper panels might yellow after years of sun exposure, though many have UV coatings to slow this. Polycarbonate can be prone to expansion/contraction, so you need to follow install guidelines (like oversize screw holes) to avoid warping noises. Also, while they handle weather well, they aren’t as airtight or insulating as a solid roof – wind-driven rain can sometimes seep at overlaps if not done carefully, and noise from rain can be loud (though diffused by plastic differently than metal). Use polycarbonate sections strategically: maybe a strip of clear panels as a skylight band in an otherwise solid roof, or if the entire shed is a greenhouse/garden shed combo. One could even do a cool modern shed with a translucent roof that glows in the evening when the inside lights are on. Just balance the look with practical concerns (like not turning the shed into a solar oven in July – consider ventilation or partial shade if large polycarbonate areas).

EPDM Rubber or Rolled Roofing: These are worth a quick mention. If your shed roof is very low slope or flat, you might opt for a single-piece membrane like EPDM rubber. It’s basically a big sheet of synthetic rubber glued down, commonly used on flat commercial roofs. For a shed, you could buy a small EPDM kit and cover the roof – it results in a seamless, leak-proof covering that’s great for low slopes. Rolled roofing (asphalt roll) is another cheap option for low-slope sheds; it’s like a big roll of asphalt shingle material that you roll out and nail down. It’s not the most durable (maybe 5-10 years life), but in a pinch, it works for a simple garden shed. These solutions are more utilitarian, used when shingles aren’t an option due to slope or cost. The appearance is plain (usually black for EPDM, mineral surface for roll roofing), but if your shed isn’t super visible or you care more about function, they can do the job. Some folks even use leftover torch-down roofing or other flat-roof materials on sheds – again, mostly for low-slope scenarios.

Clay or Concrete Tiles: Probably overkill for a shed – these are the beautiful barrel or flat tiles seen on Spanish or Mediterranean style homes. They are very heavy, requiring a beefy structure to support, and expensive. While they last long, for a shed it’s uncommon. However, if your house has a tile roof and you want the shed to match exactly, it’s not impossible. Just ensure your shed framing can bear the load (tiles can be 800-1000 lbs per 100 sq ft!). Most shed builders skip tiles due to weight and complexity.

To make a decision, weigh these factors:

- Budget: Asphalt shingles and roll roofing are cheapest. Metal and polycarbonate moderate. Wood and tile expensive.

- DIY Skill: Shingles and corrugated panels (metal or poly) are DIY-friendly. Wood shakes are harder for a novice. EPDM is moderate (like big wallpaper).

- Climate: For low slopes or wet climate – favor metal or rolled or rubber; shingles need slope. For fire-prone – avoid wood. For hot sun – consider metal (reflective) or clay; shingles and dark metal get hot, though sheds usually vent anyway.

- Maintenance: Metal and EPDM = minimal maintenance. Shingles = occasional inspection. Wood = regular upkeep. Polycarbonate = keep clean to maintain clarity and check fasteners.

- Aesthetics: Match to your house (shingles if house has shingles, etc.) or go bold if you want (a cute cedar-roofed shed can be a focal point). Metal roofs can add a splash of color. Think about how the shed roof complements the environment.

- Noise: If you’ll spend time in the shed during rain (workshop or office), note that metal and plastic panels are noisier than shingles or wood which dampen sound. You can always insulate underneath to reduce noise, though.

Many shed builders opt for asphalt shingles because it’s familiar and usually some left over from house projects. Many also love metal roofing for its longevity – especially on bigger sheds or barns where you don’t want to re-roof often. Polycarbonate is more niche, often used for specific purposes like plant nurseries or if you desire natural light. Wood is chosen mostly for style points on high-end sheds or historical restorations.

One pro tip: Regardless of material, add a drip edge (an L-shaped metal strip) along the roof edges. It’s cheap and prevents water from curling under the roof and rotting your shed’s roof decking or siding edges. Also, plan for gutters if water runoff might erode soil or cause puddles around the shed – even a small piece of gutter and a downspout into a rain barrel can be a nice addition to capture water.

We’ve covered the sky above (the roof), now let’s look at what’s below – the foundation that holds your shed up.

Foundation Options

A strong foundation is literally the groundwork for a successful shed. Your shed’s foundation keeps it level, supported, and dry. The right foundation choice will depend on the size of your shed, the terrain, climate (frost heave, drainage), and budget. We’ll explore several common foundation types: concrete slabs, gravel pads, skid foundations, and pier (or block) foundations. Each has pros and cons in terms of cost, difficulty, and durability. Laying a good foundation might not be the most glamorous part of building a shed, but it’s arguably the most important for longevity – so let’s dig in (sometimes literally!) to these options.

Concrete Slab Foundation: A concrete slab is a permanent, solid base – essentially a patio for your shed. This involves digging out an area, laying a gravel base, building a form, and pouring a several-inch-thick slab of concrete that the shed will sit on (and be anchored to). Pros: Extremely durable and stable. A well-made slab provides uniform support for the entire shed floor – no worry about sagging or settling in one spot. It’s great for heavy equipment storage or if you might roll heavy things in (lawn tractor, motorcycle) since the floor is solid. It also doubles as the shed’s floor – you can leave it as bare concrete or add flooring on top. No need for separate wood floor framing in many cases. Slabs also keep out critters (nothing can burrow under easily) and are low maintenance (sweep it clean, done). Cons: Cost and labor. Concrete can be expensive – you might spend a few hundred dollars on materials (or more, if a large slab or if you hire it out). It’s also labor-intensive: digging, mixing/pouring, finishing the surface, etc. For a DIYer, handling wet concrete and getting a smooth, level finish can be challenging without experience. Another con is drainage – a slab is impermeable, so water will run off the sides and you need to ensure it doesn’t pool around the shed edges. Also, in cold climates, an unfooted slab (called a “floating slab”) can be shifted by frost unless it’s properly built. Many regions require deeper footers (down below frost line) on at least the perimeter if the structure is large, which complicates things for a shed. And once a slab is there, it’s there – not easy to move a shed or change location. If you ever remove the shed, you’ll have a random slab unless you jackhammer it out.

To build a slab, you usually clear and level the site, then lay 3-4 inches of compacted gravel for drainage, then form and pour a slab typically 4 inches thick (often with rebar or wire mesh inside for strength). One must ensure it’s level and flat, and perhaps slightly raised or with a slight slope to shed water. A floating slab (no frost footers) is fine for small sheds in mild climates, but in freezing zones, you’d ideally have footing trenches or use piers under corners to prevent movement.

If done correctly, a concrete slab is rock-solid. Your shed can be bolted down to it with anchor bolts set in the concrete or expansion anchors after the fact, which is great for wind resistance. It’s a preferred foundation for garages or larger sheds (like over 200 sq ft) where you might store heavy stuff. However, for a basic backyard shed for lawn tools, a slab might be overkill. That said, some homeowners like that it keeps the shed super tidy and rodent-proof.

One more note: if you pour a slab, consider extending it a bit in front of the shed door as a small apron – then your doorway stays cleaner and you have a level spot to step when moving stuff in and out.

Gravel Pad Foundation: A gravel pad is a popular choice and often considered the best all-around for standard sheds. This foundation is basically a bed of compacted crushed stone/gravel that the shed sits on. It can be with or without a lumber frame border. Pros: Good drainage (water seeps through gravel instead of pooling under your shed), inexpensive, and relatively easy for a DIYer. It’s easier to get level than concrete because you can adjust and tamp the gravel. A properly compacted gravel pad can support a lot of weight and you can make it any size/shape. It’s also “adjustable” in the sense that if over time the gravel settles, you can add more or re-level it. If you ever remove the shed, the gravel can be repurposed or just left as a useful spot (no big slab to break up). Building on a gravel pad raises the shed off the ground slightly (usually a few inches), which helps keep the floor dry and away from pests. Cons: It’s not a fully solid surface – you’ll still need a floor in your shed (either the shed’s built-in wood floor or concrete blocks under skids, etc.). If not contained, gravel can spread out or wash away on slopes. Many builders frame the perimeter with pressure-treated 4x4s or landscape timbers to keep the gravel in place. Also, if the ground is very sloped, a gravel pad requires significant digging into the slope or building up a retaining wall on the lower side, which can be a bit of work. Improperly compacted gravel might settle unevenly, causing the shed to not sit perfectly level over years (but this is fixable by re-leveling the shed or adding gravel).

To make a gravel foundation, mark out an area a foot or two larger than the shed footprint (e.g., for an 8×10 shed, maybe a 10×12 gravel pad). Excavate topsoil to a depth of 4-6 inches. Fill with crushed stone (often 3/4″ minus, i.e. gravel with fines that compacts well in layers, compacting each layer firmly (a plate compactor from the rental shop does this well, or hand tamp for small pads). Ensure it’s level across and well-packed. Optionally frame the border with lumber or bricks to keep it neat. The result is like a patio of gravel. The shed can be placed directly on this if it has a wooden floor with joists or skids, or you can put concrete blocks on the gravel and then the shed on blocks.

Gravel pads are excellent for prefabricated sheds that come with a wood floor. Many shed companies recommend gravel pads as the ideal base for their pre-built sheds. They handle rain runoff nicely and prevent the shed’s wood from contacting soil. As one guide put it, a gravel pad is inexpensive, easy, adaptable to any size, and provides excellent drainage. The main maintenance is maybe re-leveling a bit of gravel if a corner settles after the first year or so.

Skid Foundation: A skid foundation means the shed itself is built on skids (think of them like two or more “runners” that the shed rests on). Often these are large timber beams like 4×4, 4×6, or 6×6 laid parallel on the ground, and the shed’s floor frame sits on or is attached to these. Many small sheds are sold as “portable” and have two skids running along the length so you can drag or move the shed if needed. Pros: Very simple – essentially integrated into the shed floor. If you’re building a shed from scratch, you can set a couple of pressure-treated beams on the ground (preferably on a gravel bed or blocks) and build your floor on those. This elevates the shed slightly and distributes its weight. Skid foundations require minimal site prep if the ground is fairly level; you can shim under skids with a few paving stones or rocks to level. They’re cheap – the cost is just the beams, which you likely need for the floor anyway. Also, being not fixed, you technically have a portable shed – you could tow it around the yard if ever needed (or easily remove it entirely). Cons: By itself, a skid on bare ground isn’t permanent or the most stable long-term. Without additional support, the shed might shift, settle unevenly, or even tip in extreme weather. Also, the wood skids touching the ground are vulnerable to moisture and rot if not properly protected (thus, treated lumber is a must, and even then you ideally want them on gravel or blocks, not directly on soil). Many times, people use a combination: skids on top of a gravel pad or concrete blocks – that way you get the simplicity of skids and some security of a foundation. Essentially, the skid foundation overlaps with other methods; it’s like a feature of the shed rather than an entirely separate foundation unless you just plop them on the ground.

Shed kits and prefab sheds often come with skid foundations designed in, as mentioned. If your shed has two long 4×4 runners at its base, placing it on level ground or a prepared surface is all that is needed. Over time, you might need to re-level by prying up a low corner and shimming or tamping more gravel under.

One notable con: not anchored. If a big wind came, a light shed on skids could possibly shift. You can anchor skids with something like auger anchors (the corkscrew stakes used for mobile homes or sheds) and screw them into the ground at the sides of the shed, then strap or chain over the skids. That can secure the shed against uplift or sliding, while still being technically movable later.

Use skids for small to medium sheds, especially if you might want to move it, or if you just want to avoid digging. Just make sure those skids are level and supported (for instance, place flat concrete pavers under each end and middle of each skid for even support). This kind of foundation is very common for, say, an 8×12 wooden shed – two 4×6 skids under it, sitting on 6-8 concrete block piers spaced along the length. Some might argue that’s actually a pier foundation (which we cover next), but the concept overlaps.

Pier or Block Foundation: This approach uses a series of isolated footings – like concrete piers, deck blocks, or masonry blocks – to support the shed at key points (corners and along beams). Think of it like a deck; you put piers or blocks and then build the shed floor on those support points. Pros: Uses less concrete than a full slab, but still provides good support and keeps wood off the ground. It’s very adaptable to uneven terrain – you can adjust pier heights to level the shed even on a slope. Piers can go down below frost line to make the shed resilient to frost heave (just like deck footings), which is useful in cold regions. With piers or blocks, you also maintain airflow under the shed, which helps keep the floor dry. If using prefab pier blocks (with a little notch for beams), installation is pretty DIY-friendly: dig level spots, maybe add gravel, set blocks, done. Cons: Each pier or block only supports a small area, so you must ensure your floor frame can span between them without bouncing or sagging. Usually, that means strong beams or closer spacing of blocks under a long span. If one pier settles differently than others, it can throw the shed off level – so careful site prep and checking level is important. A pier foundation might require more careful planning to place the supports exactly under critical points like wall studs or joists. And while you can do piers without heavy equipment (you can hand-mix concrete for a few footings or use premade blocks), it is a bit of manual labor to dig holes or carry blocks.

There are a few flavors of pier foundations:

- Concrete Pier Footings: You dig holes (usually at least 12” wide and below frost depth in cold areas), pour concrete into them – either just in the hole or using tube forms above grade – to create column supports. You might stick a metal post anchor or bracket in the top for attaching shed beams or rim joists. This is like how decks are made. These piers can be very solid – they won’t rot, and if below frost line, they keep the shed put. They do require mixing concrete and accurate placement.

- Precast Pier Blocks / Deck Blocks: These are available at hardware stores – trapezoidal concrete blocks designed to support a 4×4 post or a 4×6 beam in a slot. You set these on leveled ground (best on a bit of gravel), and can either drop a vertical post in them or lay the shed’s floor beams in the slots. They’re quick and cheap. They work best for smaller sheds (the blocks are not as stable as a buried pier, especially if ground shifts). On larger sheds, you might need many of them.

- Cinder Blocks or Bricks: Some folks use regular solid concrete blocks (like 8x8x16 masonry blocks) as piers – stacking them to needed height. This can work fine for short piers (one or two blocks high) – anything taller should likely be actual poured piers for safety. If stacking, they should be set in mortar or at least secured so they don’t shift. For a small shed, four concrete blocks (one under each corner) is a minimal foundation that can suffice for very small sheds or playhouses, but ideally you’d have more points of contact along the sides for stability.

A pier foundation is somewhat a middle ground between a slab and skids. For example, you could have 6 concrete piers, put a beam across two sets of them, and then rest your shed floor on those beams. It’s like building a mini house foundation. Concrete piers are great for sloped locations and satisfy strict code requirements. They do take more effort than a simple gravel pad, but less material than a full slab.

Which foundation to choose? Consider these scenarios:

- If you want ultimate durability and plan a heavy shed (like a garage or workshop with machinery), a concrete slab might be worth it. Especially if your shed will have frequent traffic (wheeled equipment) – the slab floor is ideal.

- If you want a solid base but at lower cost, and you have some slope: a pier foundation gives a permanent solution. You can do concrete piers at corners and midpoints, with treated beams connecting them, giving you a solid raised platform.

- For most standard yard sheds (8×10, 10×12, etc.) used for storage, a gravel pad is often recommended by pros as the best mix of cost, ease, and performance. It provides a flat, well-drained base for either a built-on skid foundation or a prefab shed.

- If you absolutely can’t do site work (say you cannot dig or pour concrete due to restrictions or renting), a skid foundation on blocks could do. You might place a few blocks on a relatively level patch of ground and set the shed on that. It’s low effort, but be prepared to adjust it over time.

No matter what, prepare the site: remove organic topsoil and vegetation where your shed will sit. Grass and roots will decompose and cause uneven settling. So even for blocks or skids, scrape off a few inches and ideally put down some compacted gravel or sand to create a stable base. This also helps with moisture.

Also, consider anchoring. If using a slab or piers, you can fasten the shed down (bolts, straps). With gravel or blocks, you might drive ground anchors at the corners. Wind uplift can affect sheds since they’re lightweight relative to houses, so anchoring a shed is a smart idea in storm-prone areas.

One more tip: Think about accessibility and moisture. If your foundation raises the shed, you’ll have a step up to get in – maybe build a ramp or step for lawn mowers or wheelbarrows. And ensure water doesn’t collect under the shed: slope the ground or gravel away or even install a perimeter French drain if you have heavy runoff. A dry foundation is a lasting foundation.

Loft Ideas for Storage and Extra Space

One of the coolest ways to maximize a shed’s utility is to add a loft. A loft is basically a partial second level or platform within the shed, usually up near the roof. It capitalizes on the often-unused vertical space above your head. Even in a small shed, a loft can provide a ton of extra storage for items you don’t need every day. In larger sheds, lofts can be spacious enough for creative uses like a small sleeping bunk or a play area. Let’s explore some loft ideas, what to consider structurally, and tips to make the most of a shed loft.

Why Add a Loft?

- Extra Storage: The most obvious use – store seasonal items, rarely used tools, holiday decorations, camping gear, etc. It’s like gaining an attic in your shed. Instead of those items taking floor space or crowding shelves, they can be tucked up in the loft. For instance, bins of winter clothes or Christmas lights can live in the loft 10 months of the year. Storage lofts can add up to 40% more storage capacity to a shed, which is huge if you’re tight on space.

- Sleeping or Relaxing Nook: If you have a larger shed that you’re maybe turning into a she-shed or a kid’s playhouse, a loft could fit a small mattress or cushions to create a cozy reading or napping spot. Imagine a tiny cabin-like feel, where a ladder leads to a loft with a twin mattress – a fun hideaway for kids, or even a spare nap space for you. (One clever idea from a shed enthusiast: use a loft as a quiet workspace or hobby area that’s separate from the main floor – climb up to do some writing or drawing in peace, with a view out a high window.)

- Hobby Storage: Lofts are great for lightweight bulky items like fishing rods, skis, or lumber. You can add hooks or notches along the loft framing to slide long items in. Or use it to store extra lawn furniture cushions, etc., during off-season. If you’re into something like model trains or crafting, a loft could even be a display area to keep your project away from the chaos below.

- Future Expansion: Perhaps you don’t need a loft now, but building one in (or at least planning for it) means you have the option later. As families grow or storage needs increase, that overhead space will be handy.

Structural Considerations

Adding a loft means adding weight up high in the shed, so it needs to be framed safely. Typically, a loft in a shed is supported by cross beams that span between the shed’s side walls. For example, you might run 2×6 joists from one wall top plate to the opposite wall top plate. These act like floor joists for the loft floor. They can rest on a ledger (a piece of wood attached to the wall that acts as a shelf for them) or be hung with joist hangers off the wall studs. Another method is to incorporate the loft into the roof trusses – some shed trusses are designed with an attic floor built in (like mini attic trusses).

A key point: don’t overload what the structure can handle. If your shed’s walls are framed with standard studs and your loft joists are reasonably sized (say 2×4 for short spans, 2×6 for longer), you can store a lot of boxes up there. But if you plan to put very heavy equipment or have people sleeping (live load), you’ll want to ensure the joists are sturdy. A shed-building guide mentioned seeing 2×6’s at 24” on center commonly for loft floors, since many shed roofs are 24” OC trusses. That can work for typical storage (maybe ~20 psf load), but if you wanted to have a person up there regularly, beefing it up to 2×8 or closer spacing might be better. It’s similar to building a small deck or the floor of a small room.

Also consider headroom. A loft doesn’t have to cover the whole shed floor – in fact, partial lofts are often more useful. You could make a loft that covers, say, the back half of the shed. That way, when you enter the shed, the front half is open to the roof (so you can stand tall), and the loft is at the back where you can stoop under it or only use that area for storage. Partial lofts are easier to access since you can reach things from the open half without crawling into a tight space. If you do a full loft (covering the entire ceiling), you maximize storage but will need an opening (hatch) and possibly have a more cramped ground floor.

Access: Think about how you’ll get up there. Common options: a ladder (either a removable ladder, a fixed inclined ladder, or even a built-in ladder rung set on the wall), or if the shed is tall enough, a small staircase or stepladder. Many just use a sturdy ladder that they hang on the wall when not needed. Some install those attic pull-down ladder kits – but in a small shed, that might be overkill or not feasible due to limited ceiling area. For frequent access, a stationary ladder or steep stairs might be warranted. Ensure whatever you use is secure; if kids will climb, safety rails in the loft are a good idea so no one tumbles out.

Ventilation and Lighting: A loft can potentially block some airflow from eave to ridge if it’s a full loft. If your shed has ridge vents or gable vents, try not to block them entirely with stored items. You might leave small gaps or use perforated loft flooring (like spaced planks) to let air flow. As for lighting, if you have windows, great. If not, consider adding a small window or vent window in the gable to let light into the loft, or use battery LED lights so you’re not searching in the dark.

Making the Most of a Loft

- Shelves and Hooks: Your loft floor underside (the joists) can be used too! Hang tools from the joists or attach hooks for bicycles, extension cords, etc. It becomes like the ceiling of the lower level, so use it for hanging storage. For example, screw in some tool hangers to the joists to hold your hedge trimmer or a coiled hose. Just be mindful of weight if the same joists are holding a lot above.

- Bins and Labels: If storing lots of small items, plastic bins or boxes are your friends. Clearly label them since lofts aren’t the most convenient to rummage around in. You might stack bins of winter clothes, labeled “Winter Gear”, “Xmas Decor”, etc., and then when the season comes, you know exactly which to bring down.

- Partial Loft with Rail: If you build a partial loft (say covering a third or half the shed), put a little railing or barrier at the loft’s edge so stuff doesn’t slide off and bonk you. Even a 1-foot high mini wall will corral storage items. As one article pointed out, a central loft hatch is better for accessing items spread out, while an end hatch maximizes floor space. So plan the opening/hatch location based on convenience.

- Loft as Platform: Some creative uses: a loft could serve as a stand for something – for instance, if you do woodworking, maybe you store lumber up in the loft. Or if you dry herbs or flowers, a loft could be a drying rack area (warm air rises, good for drying). If your shed is a chicken coop or something dual-purpose, a loft could be where chickens roost (just an idea!).

- Play Loft: For playhouses, a loft is almost a must – kids love tiny hideouts. Throw some pillows and a battery lantern up there and it becomes their clubhouse within a clubhouse. Just ensure it’s safe and maybe limit how high it is (maybe 4-5 feet above floor) so a fall wouldn’t be serious, and include a railing.

- Sleeping Loft: If converting a shed to a tiny guest space or weekend cabin, a loft sleeping area makes sense. A twin or double mattress could fit under the roof of a larger shed (12’ wide gambrel sheds often advertise this). Keep in mind egress (in a true living space, you’d want a window up there for fire escape).

Gambrel and A-Frame Advantages: As noted earlier, roof shape affects loft space. Gambrel roofs shine here because the steep lower walls give you more vertical sidewall in the loft, meaning more headroom across a wider span. A gable roof with a high pitch can also yield a decent loft but more in the center. If you know while building the shed that you want a loft, consider opting for a taller wall height or a roof style that accommodates it. Even adding, say, one extra 2×4 of height to the walls (making them 8’ instead of 7’) can make a loft more feasible without ducking too much below it.

Construction Tip: If you’re building the shed from scratch and plan a loft, you can incorporate the loft support during framing. For example, you could notch some studs to ledger boards, or install a cross-beam specifically as a future loft. Some shed plans include this. If retrofitting a loft to an existing shed, just ensure you attach to something solid – usually running supports all the way across to both long walls is best, as opposed to trying to hang it mid-air on only one side.

All in all, a loft is a fantastic way to maximize space. As one shed builder put it, it’s like a magic trick to double your floor area by using the overhead volume. Even if you only use it for lightweight storage, you’ll appreciate having that bonus area. Just be strategic in what goes up there (stuff you don’t need often) and in making it reasonably easy to get things up and down (no one likes a dangerous balancing act on a ladder with heavy boxes – if that’s the case, maybe store lighter, bulkier things like camping sleeping bags up there, and heavy stuff on ground level).

Turning a Shed into a Home Office

With the rise of remote work and the need for focused space at home, converting a shed into a home office (often affectionately called a “Shoffice” or “shed office”) has become hugely popular. It’s easy to see why: a shed office offers privacy, separation of work and home life, and the charm of a backyard retreat. If you have an existing shed (or plan to build one) and want to use it as a comfortable, productive workspace year-round, there are some special considerations. In this section, we’ll cover how to insulate and finish the shed for human comfort, handle electricity and climate control, and add those finishing touches that make it an inspiring office rather than just a glorified storage box.

Benefits of a Shed Office

Before the how-to, let’s quickly acknowledge why a shed office is awesome:

- Separation: You get a dedicated work zone that’s physically apart from the house. This helps mentally “go to work” and then “leave work” at the end of the day, even if it’s a 20-foot commute across the yard. It can reduce domestic distractions (no noisy dishwasher in the background of your Zoom, no kids barging in on calls if they know the shed is off-limits during work hours).

- Cost-Effective Space: Compared to building a home addition or renting an office, converting a shed is relatively low cost. You’re repurposing existing space. Some folks even buy a pre-made shed or shed kit specifically to turn into an office and still find it cheaper than building something from scratch.

- Customization: You can design it exactly to your needs – ergonomic desk setup, whiteboards on walls, maybe a cozy chair for reading, etc. It’s a blank slate to create your dream work environment.

- Privacy and Quiet: If your home is noisy or crowded, the shed can be a quiet haven. Likewise, if your work is noisy (musician, podcaster, etc.), you won’t disturb the household.

- Nature and Inspiration: Being in the backyard means you can look out at your garden, hear birds, and feel a bit more connected to nature than perhaps a spare bedroom office. That can be great for creativity and reduced stress.

Now, how do we transform the shed physically?

Step 1: Evaluate and Prep the Structure

If you’re starting with an existing shed, check its condition. Is it weather-tight (no leaks in roof or gaps in walls)? Is the floor solid? Any signs of pests? It’s easier to fix structural issues before you add insulation and nice flooring. This might involve patching holes, reinforcing framing, or even leveling the shed if it’s settled. Ensure the shed is up to the task of being an occupied space: a door that opens/closes smoothly, maybe existing windows for light (if not, consider adding a window or two for natural light – offices need it).

Some locales might still require a permit to officially “finish” a shed, especially if running electricity. Usually interior work on a shed isn’t heavily scrutinized, but adding power often does require an electrical permit. Also, if you’re in an area with building codes, converting a shed to an office (which is a habitable space) could trigger different requirements (like emergency egress window, certain insulation, etc.). Often people do this informally, but keep it in mind if you want everything legit.

Step 2: Insulate and Weatherproof

This is key. An untreated shed is too cold in winter and too hot in summer for comfortable work. Insulation will regulate temperature and also help with soundproofing a bit (so you don’t hear every lawnmower or have your phone calls heard across the fence).

Common ways to insulate a shed:

- Walls: Most shed walls are 2×4 studs, sometimes 2×3. You can fit fiberglass batts in the cavities easily (e.g., R-13 for 2×4 walls). Alternatively, rigid foam boards cut to fit between studs work well and can provide a bit higher R-value per inch. Spray foam is top-tier for insulation and sealing, but can be pricey for a small project (unless you use the minimal expanding kits). Foam board is a popular DIY choice: cut panels, insert, use spray foam gap filler around edges to seal. The important part is to also install a vapor barrier on the warm side (usually that’s the inside in winter climates) if you use fiberglass, to prevent moisture issues. Some rigid foams double as a vapor barrier if seams are taped. Since sheds can be prone to moisture, sealing gaps is important – use caulk or foam to close up cracks in the shell before insulating.

- Roof/Ceiling: Don’t neglect the roof – hot air rises, and in summer the sun beating on the roof can superheat the shed. If you have an open ceiling (no attic), you can insulate between rafters. Make sure to leave an air gap above the insulation for ventilation if it’s a pitched roof (baffles at eaves to allow airflow from soffit to ridge). Many do rigid foam here too, as it both insulates and can act as a radiant barrier if foil-faced. If you have a loft, insulate the loft floor (which is the ceiling of the main area). If you’re not insulating the roof, at least insulate the ceiling plane. For a gable roof, you might also put some batts up in the gable peak area. Good insulation in the roof will keep it cooler in summer and easier to heat in winter.

- Floor: If your shed has a raised wood floor with joists, consider insulating underneath it. This is trickier if the shed is already on the ground, but you might crawl under (or remove floorboards if accessible) to put batts or rigid foam between floor joists. If the shed sits on a slab or on the ground, you can’t really insulate below, but maybe put a rug or insulated flooring (some use foam underlayment and then plywood or laminate). While floor insulation is somewhat optional (heat rises, after all), a cold floor can be uncomfortable on your feet and could chill the space. At minimum, have a good floor covering.

- Windows & Door: If the shed has very thin single-pane windows, you may want to upgrade them to double-pane for better insulation (or at least add a storm window or use shrink-film in winter). The door might need weatherstripping to seal drafts. You could even swap a thin shed door for an insulated exterior door (maybe a salvaged one cut down to size). Weatherproofing all openings (gaskets, caulk around window frames) will make a big difference in keeping the shed cozy.